Diego Rivera Dream of a Sunday Afternoon Ap Art History

Diego Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central), 1947, iv.8 x 15 m (Museo Mural Diego Rivera, originally, Hotel del Prado, Mexico City; photo: Fedaro, CC Past-SA 4.0)

Dream or nightmare

In Dream of a Dominicus Afternoon in Alameda Cardinal Park, hundreds of characters from 400 years of Mexican history get together for a stroll through Mexico Urban center'south largest park. But the colorful balloons, impeccably dressed visitors, and vendors with diverse wares cannot conceal the darker side of this dream: a confrontation between an ethnic family and a police force officer; a man shooting into the confront of someone being trampled past a horse in the midst of a skirmish; a sinister skeleton grin at the viewer. What kind of dream, or nightmare, is this?

Diego Rivera, detail with rearing equus caballus and shooting, Dream of a Sun Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Key), 1947, 4.8 x 15 m (Museo Mural Diego Rivera, originally, Hotel del Prado, Mexico Metropolis; photo: Garrett Ziegler, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Surreal quartet

In the spirit of Surrealism, this is a complex dream. For Surrealists, similar Salvador Dalí, dreams were the principal subject area matter. Since dreams are so personal and foreign, this immune artists to juxtapose unrelated matter, similar clocks and ants for Dalí. Though Rivera never officially joined the Surrealists, he uses this approach in Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park as he cobbles together a scene composed of disparate historical personages, including Hernán Cortés (the Spanish conqueror who initiated the autumn of the Aztec Empire), Sor Juana (a seventeenth-century nun and ane of Mexico's most notable writers), and Porfirio Díaz (whose dictatorship at the plough of the twentieth century inspired the Mexican Revolution).

Diego Rivera, detail of cardinal group with four rightmost figures (correct to left) being the printmaker José Guadalupe Posada (right), La Catrina (the Skeleton), the painter Frida Kahlo (backside La Catrina), and the artist equally a young homo (in front of Kahlo), Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Cardinal), 1947, four.eight x xv 1000 (Museo Mural Diego Rivera, originally, Hotel del Prado, United mexican states Metropolis; photograph: Garrett Ziegler, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Perhaps the almost striking group is a central quartet featuring Rivera, the artist Frida Kahlo, the printmaker and draughtsman José Guadalupe Posada, and La Catrina. "Catrina" was a nickname in the early twentieth century for an elegant, upper-grade woman who dressed in European clothing.

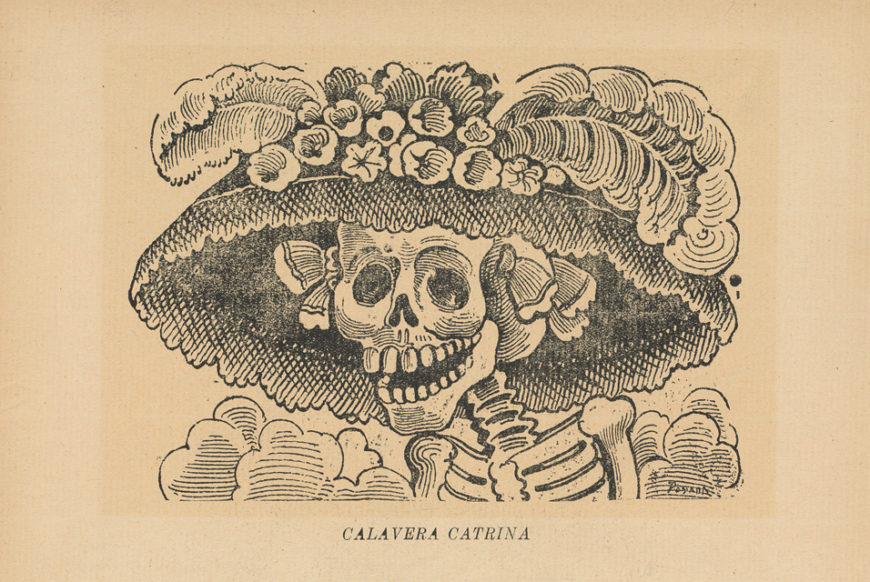

José Guadalupe Posada, La Calavera Catrina, 1913, etching, 34.five 10 23 cm (photograph: Wmpearl, public domain)

This character became infamous in Posada'due south La Calavera de la Catrina (The Catrina Skeleton), 1913. Here, the renowned printmaker depicted La Catrina as a skeleton in order to critique the Mexican elite. In Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park, Rivera reproduces the original Posada print and adds an elaborate boa—reminiscent of the feathered Mesoamerican snake god Quetzalcóatl—around her neck.

La Catrina unites two great Mexican artists in this mural: she holds Rivera's paw as her other arm is held past Posada. Though Posada died in obscurity in 1913, artists later brought attention to his work and he was a meaning influence on the Mexican muralists. The fourth character in this quartet is Kahlo. She stands behind a kid-version of her husband, with one mitt protectively on his shoulder as her other holds a Yin and Yang object.

Diego Rivera, particular with the artist equally a young man (lower left), the paintier Frida Kahlo (backside him), and La Catrina (the Skeleton), Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central), 1947, 4.8 ten 15 thousand (Museo Landscape Diego Rivera, originally, Hotel del Prado, Mexico City; photograph: Adam Jones, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In Chinese philosophy, Yin and Yang refers to opposite still interdependent forces, like day and night. Within the name of this concept is possibly the most cardinal duality in humanity: female ("Yin") and male ("Yang"). Thus, this Chinese symbol becomes a metaphor for Rivera and Kahlo's complex relationship: Rivera began equally Kahlo's mentor; they then married, separated, and got back together; they were political comrades; and they painted each other frequently. Their double-portraits often reflect the state of the couple'due south relationship at that moment. In Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931) Kahlo subtly plays with the couple'south stature in order to emphasize Rivera's influence on her. Kahlo was ill as Rivera worked on this mural and his diminished size may reflect his feelings of helplessness.

Reading Mexican history

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931, oil on sheet, 39–3/8 10 31 inches or 100.01 ten 78.74 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: Lluís Ribes Mateu, CC Past-NC 2.0)

Stepping away from the center, if one reads the mural like a text, a chronology emerges: the left side of the composition highlights the conquest and colonization of United mexican states, the fight for independence and the revolution occupy the majority of the central space, and modern achievements fill up the right. For some fine art historians the central area is a snapshot of bourgeois life in 1895—as refined ladies and gentlemen promenade in their Lord's day best, nether the watchful eye of Porfirio Díaz in his plumed war machine garb. One gets a sense of the inequality that stirred boilerplate Mexicans to overthrow their dictator and initiate the Mexican Revolution which lasted from 1910 until 1920.

In this light we can appreciate the dreams and nightmares within each epoch. To the left of the balloons the nightmares of the conquest and religious intolerance during the colonial-era give way to the dream of a democratic nation during the nineteenth century, represented past the over-sized effigy of Benito Juárez, who restored the republic after French occupation and attempted to modernize the land as president. On the correct of the composition, across the bandstand, the battles of the revolution give way to a society where "land and freedom," as championed by the workers' flags, becomes a tangible reality.

Diego Rivera, detail with Benito Juárez summit center, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park (Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central), 1947, 4.8 10 15 m (Museo Mural Diego Rivera, originally, Hotel del Prado, Mexico City; photo: Fedaro, CC Past-SA 4.0)

Histories normally edited out

More often than not history is written past the victor and thus reflects an incomplete story. Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park is an antitoxin to this: Rivera guarantees that histories ordinarily edited out (the stories of the indigenous and the masses) have a place in this one thousand narrative. The artist reminds the viewer that the struggles and celebrity of four centuries of Mexican history are due to the participation of Mexicans from all strata of gild.

Additional resources

William Stockton, "Rivera Mural in Mexico Awaits Its New Shelter" in The New York Times, Jan. four, 1987

Source: https://smarthistory.org/rivera-dream-of-a-sunday-afternoon-in-alameda-central-park/

0 Response to "Diego Rivera Dream of a Sunday Afternoon Ap Art History"

Post a Comment